|

|

|

|

| Horie was first developed 300 years ago when a canal

was built and opened as a new transportation route. The district

flourished during the Edo period as the entertainment center after

Wako-ji Temple was established in the area and became a place of

religion and recreation for people of old Osaka, where a variety

of entertainment shows and events were held. While the landscape

of Horie has dramatically changed with the times, the temple, or "Amida-ike-san," has

been cherished by the locals and is still standing today as a witness

of the transition of the community. As we trace the history of

Horie we can see how life was spent around the temple's symbolic

pond and we find a new and important perspective from which we

may reconstruct the multi-layered image of this unique community. |

|

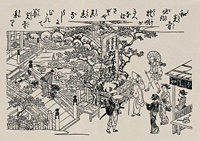

“Naniwa no nagame”(A view of old-time Osaka), Wako-ji Temple

Originally, Horie was the least

developed swampy area in old Osaka. Bordered by the waters

of the Nagahori Canal to its north, the Nishiyokobori Canal

to its east, the Dotonbori Canal to its south, and the

Kizu River to its west, the roots of the district first

occurred in the very early Edo period. The development

was concentrated on the riverside and the inland area was

left untouched for a while until Kawamura Zuiken built

the Horie Canal that runs through the center and Wako-ji

Temple was established in 1698(Genroku11) in a newly developed

quarter named Horie Shinchi (new land). Amida-ike(Amida

Pond) is located in the spacious grounds of the temple.

“Dozo Amida-sanzon Ryuzou” (standing bronze statues of Amida-sanzon),

Wako-ji Temple

The name of the pond is derived from

a legend of an ancient statue of Amida (Amitabha) Buddha,

which is believed to have been brought to Japan from

Baekje (ancient Korea) in the 6th century. The statue

was once disposed of in the pond during the anti-Buddhism

movement but was recovered by a man named Honda Yoshimitsu,

who took the statue back to his home in Shinano (today's

Nagano Prefecture) and later dedicated it to local Zenko-ji

Temple. Based on this legend, a Buddhist monk, Chizen,

regarded Horie as a holy place and established Wako-ji

Temple. The image of the temple's deity, which is Amida

Buddha, is housed in a hall that floats on the pond.

The temple has been affectionately called "amida-ike-san" by

local people and has been a place of worship for them

since.

To collect funds for investment in the development of Horie, the

Edo Shogunate gave a variety of priorities to the district to encourage

local businesses, by permitting shipping licenses and allowing

the opening of markets, for example. The district evolved as the

lumber industry flourished on the riverside of the Nagahori Canal,

which became known as Zaimokuhama and served as the nation's trading

center of lumber. By the end of the Edo period, related manufacturing

industries of furniture, Buddhist articles, and ranma (wooden decorative

transom) were also established.

During the Edo period, making a

visit to a temple was one of the few leisure activities available

to the common people. Unlike today, in which a variety of entertainment

and amusements are available, people of those days had only limited

recreational choice and visiting temples therefore was a rare and

important occasion for them to satisfy their spiritual needs, enjoy

a break, and relieve themselves from daily stresses. Temples at

that time were not only the place of worship but also the destination

for leisure.

Temples also tried to attract more visitors in various ways.

At Wako-ji Temple, both inside and outside of its grounds were

filled with entertainment stages, game arcades, show tents, and

street vendors. Its lottery and plant fair also became popular.

It was as if parks, theaters, and museums were all located within

the temple. Wako-ji Temple gradually became the local center

of entertainment. |

|

“Kinryusan Sensoji hogaku shukuzu (the 12th yokozuna Jinmaku Kyugoro)”, Nihon Sumo Kyokai Sumo Museum Horie is also known as the

origin of Osaka zumo. Although Sumo became

a popular entertainment during the Edo period, the Tokugawa

government prohibited its promotion as business because

of frequent disturbances and fights among the audiences.

Instead, it was allowed only to be held as kanjin zumo,

or a fund-raising event for temples and shrines. While

the word kanjin originally means to encourage

people to follow the Buddha's teaching towards good deeds,

it was commonly understood as an encouragement of donation

to help temples build a new statue or repair old buildings.

Because of its popularity, sumo became a good source of

revenue for the temples to cover various expenses.

Osaka zumo started as

a promotional event for the development of Horie Shinchi.

While the Edo government led the development of the district,

it divided the land and assigned lots to private developers

via bidding. In order to attract new people to the area

and to ensure the district prospered, local merchants of

Horie asked the government for permission to operate sumo tournaments.

The first sumo tournament in Osaka was held in

1702 (Genroku 15) near the present Minamihorie Park.

According to records, the 13-day tournament series was very successful

and became quite a profit-earning event for the local developers.

Since then, businessmen as well as sumo wrestlers began to sponsor

and hold sumo matches and tournaments in the grounds of temples

and shrines by bringing wrestlers from all over the country. Horie

was the center of Japanese sumo tradition. In 1765 (Meiwa 2), after

the government permitted the operation of kanjin zumo in Namba

Shinchi, the tournaments were held alternatively at these two locations.

Supported by the economic power of Osaka merchants, the popularity

of Osaka zumo once well surpassed that of Edo zumo. By the late

18th century, however, it became an annual routine to hold winter

and spring tournaments in Edo and one around summer in Osaka and

Kyoto. As major wrestlers moved to Edo, Osaka zumo gradually lost

its popularity by the end of the Edo period.

In addition to sumo, the Edo government encouraged Noh and Bunraku

theaters as well as the operation of machiai-jaya (tea houses)

to promote the development of Horie Shinchi, located on the north

side of the Horie Canal. Toyotake Konotayu performed a Ningyo Joruri

(Japanese puppet show) in Horie and gained popularity comparable

to that of the Dotonbori theater district. The establishment of

machiai-jaya led to the growth of the sex entertainment industry

and attracted crowds to districts like Shinmachi, a popular red-light

quarter in Osaka. The name of Horie was depicted in a number of

stories of Ningyo Joruri theaters and Ukiyo Zoshi.

|

|

| In the northeast corner of the Horie district where the Nagahori

Canal and the Nishiyokobori Canal used to cross, there were four

bridges, one upstream and one downstream of each river, built to

form a square shape around the crossing point. Known as Yotsuhashi,

the four bridges were once a symbolic landmark in a tranquil scene

of Horie 300 years ago, as it was depicted in a haiku poem by a

local poet, Konishi Raizan: "Suzushisa-ni Yotsuhashi-wo Yottsu

Watarikeri (as the breeze from the rivers was so comfortable that

I kept walking until I crossed all four bridges and came back to

where I started)." |

Yotsuhashi (Meiji period): Image from Furusato Omoide Shashinshu: Meiji, Taisho, and Showa Osaka (Vol. 2) Published by Kokushokankokai

Yotsuhashi (Showa period): Image from Furusato Omoide Shashinshu: Meiji,

Taisho, and Showa Osaka (Vol. 2) Published by Kokushokankokai

Yotsuhashi (today) |

At the turn of the 20th century, railroad networks started

to grow as the new transportation that would soon take over from

the barges on the rivers. In the Horie district, the Namboku

Line along the Yotsubashi-suji Avenue and the Tozai Line along

the Nagahori Canal were developed by the city government. Minatomachi

Station on the Kansai Tetsudo Line and Shiomibashi Station on

the Koya Tetsudo Line also opened along the Dotonbori Canal.

Thanks to this convenient transportation, the Horie district

continued to evolve both as a residential area and as an entertainment

center where various amusement facilities were located.

Although the Horie district was completely burnt down by bombings during World

War II, the community gradually recovered with local industries including lumber

trade and furniture manufacturing as well as entertainment businesses in Horie

Shinchi regained their strength. During the years of postwar economic growth,

furniture dealing businesses along the Tachibana-dori Avenue flourished at an

unprecedented pace. Meanwhile, the view of the town dramatically changed as the

main traffic routes shifted from water to land. The Horie Canal was filled and

made into a road in 1960 (Showa 35), followed by the Nagahori Canal in 1964 (Showa

39) and the Nishiyokobori Canal in 1971 (Showa 46). The lumber industry moved

to the suburbs and the red-light quarter was closed and transformed into office

buildings and car parking facilities. Furniture businesses along the Tachibana-dori

Avenue waned as more people moved to the suburbs and large-scale furniture stores

opened targeting the increasing suburban population.

In recent years, however, the Horie district has been gaining a refreshed vitality.

Since the late 1990's, a number of cafes, galleries, and specialty stores have

been opened on the Tachibana-dori Avenue. Large-scale high-class goods stores

in Tokyo have also opened their branch stores in the area. Even some of the older

furniture stores have changed themselves into fashionable interior decor shops

targeting younger generations. Office space for small businesses and SOHOs are

increasing, attracting designers and creators.

Wako-ji Temple lost its buildings, including its main hall, during

the war. A temporary main hall was built in 1947 (Showa 22) and was used until

the main hall was rebuilt in 1961 (Showa 36) with the support of local lumber

industry and donations. Legendary Amida Pond (Amida-ike) still exists today as

a historical witness of Horie, which once flourished as the water capital.

To gain a true feeling for the history of the town, you just might

be able to visit Amida Pond (Amida-ike) and pick up the “vibes” of the old community

even today, even as they are starting to fade into the background of what is

today’s modern world.

*This article was also featured in "horie bon!”, a

community magazine issued by the Horie Machizukuri Committee. |

November 29, 2007

Hiroshi Yamanou, Osaka Brand Center |

| |

|

|